Are commitments to localism in Ukraine just lip service?

Russia’s aggression in Ukraine not only shows the failures of multilateral institutions to stand strong for democracy and human rights, it also reveals cracks in the international humanitarian system where over-professionalised, project-driven approaches, standards and practices are often undermining cooperation, solidarity, inclusion, agility and innovation.

Latvia, just 900km away from Ukraine, has been a neighbouring safe haven for more than 22,000 Ukrainian refugees since the outbreak of the Russian war. Unprecedented levels of support – millions in cash and in-kind donations from different organisations, people and the private sector as well as countless volunteering hours given by people across the country – have been mobilised to meet the endless humanitarian needs, both of refugees in Latvia and those in Ukraine. However, despite this enormous effort, this fully locally led, managed and funded work lives a parallel life because it does not quite fit in or “qualify” to be part of the broader international humanitarian response.

Going unheard

As the director of the Latvian Platform for Development Cooperation (LAPAS), the equivalent of Bond in the UK, I have approached several international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) since the beginning of the war with the aim of collaborating with, and being looped into, the international humanitarian responders’ “bubble”. We have needed help, support, and potentially a small slice of generous international aid to sustain our work. But we’ve received deep silence. And it is not just us. Recently I met a Ukrainian activist at a global-level event who said she felt relieved to finally find someone who did not just listen but actually heard what she was saying.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsThis is entirely contradictory to the commitments that have been made to localised humanitarian responses. It reveals a failure to recognise and value local actors’ knowledge and our understanding of local context, culture, language and politics.

Contested knowledge

At the beginning of my European-level work on development and humanitarian issues, which is dominated by large European INGOs, I was constantly corrected whenever I made a proposal. Phrases like “we call it…” and “probably you meant…” were common. The message was clear: I was not from the European bubble so I did not understand. Despite having been the director of LAPAS since 2012, bringing together more than 30 Latvian NGOs and networks and sitting on the Board of Forus, still I am told this.

A few months ago, just as I returned from a conference where I was told that I am “not certified to understand” and that the humanitarian assistance system is functioning well, my colleague sent more than 700 donated cars to Ukraine. I reflected: should we have done nothing because we are “not certified to understand”? No – we asked Ukrainians directly what they needed and then found ways to deliver it.

Over-professionalisation, and turning humanitarianism into a fierce competition for contracts and management fees, is pushing out local actors who have the first-hand, context-specific capacity and knowledge to act. Even if and when capacity building is necessary, it should not be about glossy certificates with well-known names, but a willingness to work together, support and learn.

The advantage of agility

Big humanitarian players may have billions worth in pledges from generous donors but they have lost something that we have – agility. Feeling a direct sense of urgency and desperation, yet being forced to work with no funding and no significant external support – and therefore no rigid project plans and logframes – means we are able to find solutions and innovate.

For instance, when Covid-19 started in Latvia I joined a “hackathon” to look for IT solutions to address the pandemic’s health and social challenges. As a result of this unusual collaboration, a nationwide volunteers’ movement, managed by a mobile app and a call centre, was born, and people who had been made vulnerable got the help and advice they needed.

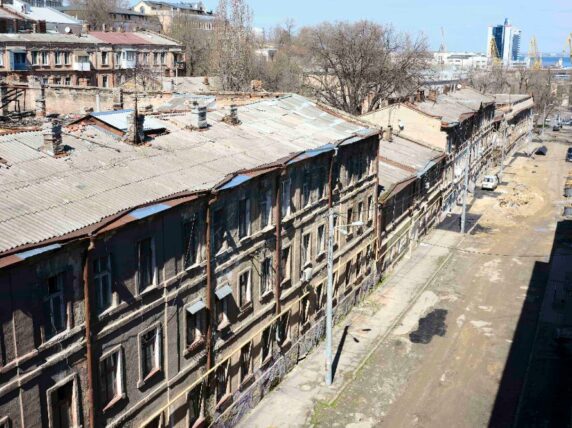

To address growing humanitarian needs in Ukraine I have built an agile team of professionals outside the NGO sector who are driven by passion and the cause. We have helped refugees and opposition figures from Belarus and sent more than 25 humanitarian aid cargos to Ukraine. And we’ve done this while operating with almost no money, relying mainly on in-kind contributions and volunteers.

Doing the work

A few years ago an international prize was given to a women’s initiative and the moderator curiously asked the recipient what the project behind the activity was. The woman smiled and answered: “No project, we do not have time for projects, we do the work.” This is the essence of my volunteering experience during the last few years – I just go and do the work. Interestingly, my closest partners are the “unusual” allies of the private sector and government. We sit at one table and look for the best solutions. And I am proud to succeed, to learn and to change.

If the broader INGO sector starts to feel irrelevant to us, there is a real risk that the INGO bubble may get detached from realities on the ground and face a serious challenge of legitimacy. Technological development and rising education levels are fostering more and more direct participation, resulting in vibrant grassroots initiatives that solve problems gaining increased visibility and support from the public. This changing situation requires a new kind of international humanitarian system. One where local actors are not marginalised but put at the centre and are adequately recognised and supported.