UK aid: Exploring the positives amidst cuts and challenges

It has been a difficult few years for UK aid advocates. Three years of fierce cuts have all but shattered the UK’s reputation as a development leader.

A recent Equality Impact Assessment carried out by Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FDCO) officials outlined the extent of the impact. The cuts had a severe impact on marginalised groups and countries in crises and jeopardised the UK’s ability to meet its international commitments. Furthermore, attempting to unravel the impact became more difficult in recent years as FCDO stopped publishing forward-looking allocations and uploading data to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), undermining its previously solid reputation for transparency.

However, there have recently been signs that the FCDO might be on the verge of turning the corner. The recently published annual report for 2022-23 contained much more information on future allocations than in previous years and appears to indicate a greater concern with countries that are most in need. While there is still a lot to improve upon, this blog looks at some of the main takeaways from the report and argues that finally, the news is not all bad.

Regaining a reputation for transparency

FCDO seems intent on regaining its position as one of the most transparent aid departments. In the past, it has always been one of the few agencies to report usable data to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), the platform that allows providers to report aid in near real-time. However, the quality of its reporting dropped substantially in 2022, as the FCDO stopped uploading data while it was going through a process of merging ex-FCO and ex-DFID reporting systems. In contrast to previous years, the 2022 annual report had scant information on future allocations.

In 2023, there were improvements on both counts. The 2023 annual report returned to a full breakdown of allocations by country and priorities for the next few years, giving a sense of how FCDO’s priorities will change in the near future. In addition, the hiatus from uploading data to IATI has finally ended. While there are still gaps in the data that FCDO reported in 2022, they have promised to return to a monthly uploading cycle.

Improving poverty focus

Beyond the rapid shrinking of the Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget in recent years, analysts have also been concerned with the increasing use of ODA for diplomatic and political motives. While never absent from aid policy, these were made more prominent in documents such as the 2022 Strategy for International Development, which has also coincided with a decline in the poverty focus of UK aid. Between 2010/2011 and 2021, the share of UK aid going to least developed countries (LDCs) declined from 37% to 26% according to the OECD (including the share that LDCs receive from multilaterals that is attributable to the UK).

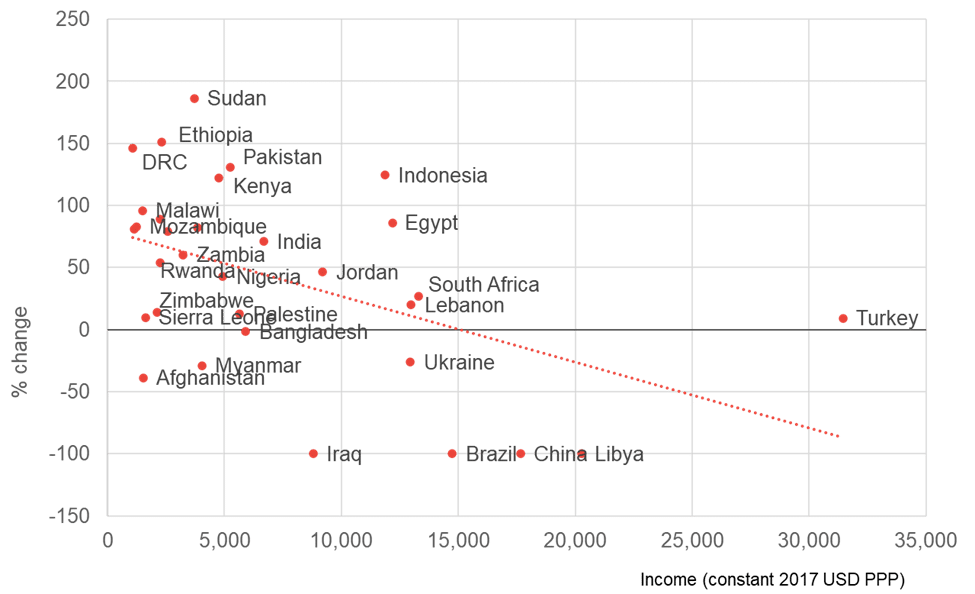

This trend looks set to be reversed according to the FCDO’s budget allocations for the next few years. While these allocations do not outline the total ODA that will be received from the UK (partly because the report doesn’t include ODA from other departments, and partly because countries will receive additional aid as part of the programmatic priorities such as gender and climate), they do give an indication of FCDO’s changing priorities. The share of aid allocated to low-income countries (LICs) will increase from 53% in 2022/23 to 57% in 2024/25. Increases in allocations between these periods are well-correlated with how poor countries are, and several relatively wealthy countries have seen their allocation drop to zero.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsChange in FCDO country allocation against GDP per capita, between FY22 and FY24 constant 2017 PPP USD

Source: Development Initiatives analysis of FCDO Annual Report and Accounts 2022 to 2023 and World Bank Development Indicators. (Note: FY22 refers to the period from April 2022 to March 2023).

Is the UK Treasury still pulling strings?

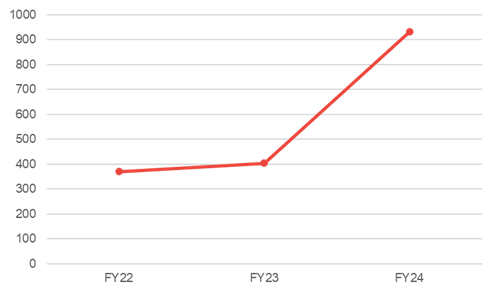

Not everything in the report is worth celebrating though. There are signs that the UK Treasury’s preoccupation with making the fiscal deficit appear lower (“fiscal gimmickry”) is still driving decision-making. Take British International Investment (BII), the UK’s development finance institution. BII makes great investments and should be seen as an important part of the UK’s development toolbox, and by some measures is more poverty-focused than the UK’s overall ODA budget. Nevertheless, a three-fold increase in its allocation between 2022/23 and 2024/25 looks suspicious, especially given that BII contributions were relatively insulated from recent cuts. Is this decision really being driven by development effectiveness, or by the fact that contributions to BII create an asset and so don’t add to the UK’s deficit?

BII allocation by fiscal year, £m

Source: FCDO Annual Report and Accounts 2022 to 2023. (Note: FY22 refers to the period from April 2022 to March 2023).

Similarly, FCDO appears to be planning a huge increase in the share of regional bilateral aid which is spent on capital goods, which also don’t add to the deficit (think schools and hospitals, rather than teachers and nurses). These are undoubtedly necessary, but the rapid increase from 8% of regional bilateral spend in 2022/23 to 46% in 2024/25, suggests that again, accounting rules are driving spending decisions.

Taking positives where we can find them

The FCDO’s annual report does not signal a full return to leadership in global development. FCDO’s ODA budget will remain subdued in 2023, primarily because in-donor refugee costs will remain elevated. A return to 0.7% still looks far away, and on issues beyond aid such as recycling Special Drawing Rights or multilateral reform, the UK still lags behind most of its peers.

Nevertheless, after three years which have been nearly completely bereft of good news on UK aid, it is worth highlighting some of the positives when they come.

Category

News & Views