Two weeks of Official Development Assistance (ODA) statistics: what have we learnt?

The UK government has published two sets of data in the last two weeks which provide information on how ODA is being spent and on what.

Last week, Andrew Mitchell shared the 2022-23 and 2023-24 Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) bilateral allocations, i.e. ODA allocated to a specific country, programme or region, in a statement to parliament.

Yesterday, the FCDO published the Statistics on International Development: Provisional UK Aid Spend 2022 (SID). These provide an initial overview of how the UK and FCDO spent ODA in 2022. So what did we learn from both sets of data about what the government’s priorities and strategy look like, when it comes to international development and humanitarian assistance?

Looking back – the people in low-income countries lost out as spend in the UK increased

The SID confirmed that UK ODA in 2022 was £12.8bn, meeting the 0.5% target. While this was an increase of £1.4bn compared to 2021, it is still £4.7bn less than would have been spent had the 0.7% target been met. This represents a massive drop in funding at a time when global poverty, insecurity and inequality have increased.

Even this reduced amount has been further slashed by huge increases in ODA spent in the UK. An astonishing £3.7bn was spent on in-donor refugee costs in 2022, an increase of 250% (£2.6bn) since 2021 and 487% (£3.1bn) since 2020. This is more than the FCDO spent bilaterally in Africa and Asia combined, and three times larger than the total humanitarian assistance budget. These costs were largely spent by the Home Office, whose budget increased by 130.2% to £2.4bn, but the Department for Health and Social Care, Department for Education, Department for Work and Pensions and Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities all saw huge increases to also accommodate their increased spend on refugee and asylum costs.

To accommodate this raid on the ODA budget, the proportion spent by FCDO has dropped to 59.8%. Alarmingly, this is the first time the FCDO (or DFID beforehand) has spent less than 70% of the UK’s ODA budget. Despite an increase in overall ODA between 2021 and 2022, the FCDO’s ODA fell by £539mn. This meant a reduction of £258mn in bilateral spend to Africa (19%) and £127mn to Asia (12%). It also meant a cut of £950mn (22.2%) in UK spending through multilaterals.

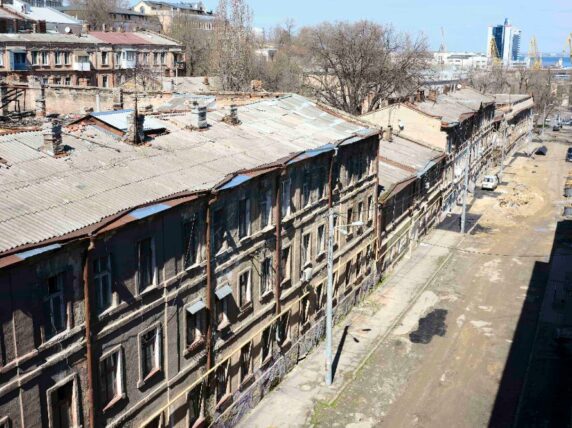

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan have a further impact on ODA in 2022. Bilateral humanitarian spend increased by £317mn (42.6%) to just over £1bn. The increase is welcome, but it does not adequately address the growing humanitarian need around the world and is not close to the £1.5bn provided in 2019. Support to Europe increased by £249mn (405%), largely due to our increased support to Ukraine. Though needed, it should not come at the expense of those living with the impact of poverty, climate change and conflict globally.

The use of the ODA budget to cover our domestic costs is unacceptable, we should use our domestic budgets to cover this activity, and the people who are most marginalised around the world are having development and humanitarian support taken away as a result. With increasing food insecurity, conflict and climate change impacts, it is wrong and short-sighted to shift the focus of our ODA spend away from its original purpose of poverty alleviation in low- and middle-income countries.

Looking forward – “difficult choices” and prioritisation of UK investments

Andrew Mitchell acknowledged that the increasing demands on the UK’s ODA budget have necessitated “difficult choices”. This is an understatement. The choices made reveal a lot about the government’s current priorities. Whilst the 23-24 FCDO ODA budget is set to increase to £8.1bn, this is still a cut of £2bn from the £10bn that was originally planned.

The budget is structured around FCDO Director General teams, so we can only see how different teams are changing their spending plans. It’s difficult to draw definitive conclusions, as a reduction in one team’s spending may not mean a cut overall – that spend might have been picked up by another team. Some things stand out though. Spending through the Afghanistan and Pakistan teams has been cut by 53% between 22-23 and 23-24, with just £141.9m planned for the upcoming year, compared to £304.4m last year. Other teams seeing significant reductions to their budget include the research and evidence team (57% less than the previous year), economic security team (52% less), development and parliament (41% less) and global health and covid (28% less). The Africa teams have had their budget cut by £118m (15%). The majority of teams are having their budgets reduced.

Mitchell states they plan to spend £1bn on urgent humanitarian needs in 23-24. Despite a growing need for humanitarian support around the world, this is the same as what was spent on humanitarian assistance in 2022.

Though the majority of teams are receiving cuts, some are receiving increases. The government’s plan is to increase spend to multilateral organisations by £663m (20%) while cutting bilateral spend by £320m (13%). This may in some part rectify the cuts to multilateral spend this year, and we welcome the UK using its multilateral role to influence international institutions for good, but it does not need to come at the expense of bilateral spend. The government is also clearly prioritising its private investment vehicles – spend through British Investment Partnerships is set to increase by 104% to £109m, and the category ‘financial transactions’ (British Investment International) is increasing by 35% to £143m. Prioritising institutions and finance investment vehicles, often in the form of loans, guarantees and equity over direct bilateral spend, mostly in the form of grants, is a strategic choice. This is worrying. Investment in private sector development has an important role to play in poverty alleviation, but we need transparency, accountability and greater coherence with the SDGs to ensure investments are truly delivering for marginalised communities. This should not replace bilateral grant funding in addressing the most basic needs of those living in poverty.

What next?

Next year is going to be another painful one for UK aid partner communities and organisations. These continued cuts do not need to happen. The UK government must urgently stop using the ODA budget to cover domestic costs, must prioritise the existing budget to address poverty and inequality in low- and middle-income countries and plan a return to 0.7% GNI. There are some hopeful signs – Andrew Mitchell has stated that the ODA Board, chaired by him and the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, will more effectively scrutinise ODA spending, generally interpreted as a move to avoid the increasing ODA spend by the Home Office. We hope this will be the beginning of ODA becoming more focused on its main purpose of eradicating poverty and inequality globally.