Challenging harmful visual narratives through images

Images have been one of the most impactful tools for storytelling. Humans have always shown a strong association to images.

Our dreams, imagination and memories take the form of images. In some cultures, meditations and Yogic practices use images as a portal to transcend into another time and space. We have used images to tell the story of humanity for thousands of years, and have explored image based media, such as movies, photography, paintings and comics, to document our history for future generations.

Yet we are living in an era of infodemics, with social media platforms dissipating images, photographs and opinions globally, within seconds, to trigger emotional reactions. There’s no denying that these disposable images, meant for one-time consumption, are forming a new narrative for the ‘story of humanity.’ Unfortunately, with humanity facing a raging pandemic, climate change and oppressive systemic policies, visual media can leave people feeling powerless and hopeless about the future.

A lot of well meaning NGOs tend to represent their work with images that trigger strong emotions because of their click-bait potential. In societies where people are becoming more and more disconnected from each other, these images can engender feelings of despair and discontent, as well as fear, guilt -due to personal privileges- and even resentment towards other communities. Something very insidious happens when we consume these images for years without question: we subconsciously start believing them, and that is how most oppressive systems thrive.

Let us consider the representation of gender-based violence, where focusing on a woman’s moment of violation has become the norm. Most are familiar with the image of a woman, cowering in a corner, while an anonymous shadow, or a pair of hands, lurk over her. Equally, the face of a bruised woman is also a well-established image used in campaign media, which aims to raise awareness of gender based violence. In both instances, the perpetrator doesn’t have a face or is entirely missing from the picture. Meanwhile, the women are portrayed as helpless victims, hiding their faces in shame, fear and/or guilt.

These images are highly sensationalised, insensitive and triggering to women, especially those with experiences of abuse. Sexual and/or gender based violence is usually about re-establishing power. It’s about showing the women their place. Aren’t these images doing the same? Furthermore, we do not need to remind women what trauma looks like, especially when most women have photographic memories of their own trauma.

A similar pattern emerges when we consider the representation of the Global south. In this case, the male gaze is replaced by the white colonial gaze.

While images reflect the narrative, they also shape the larger narrative

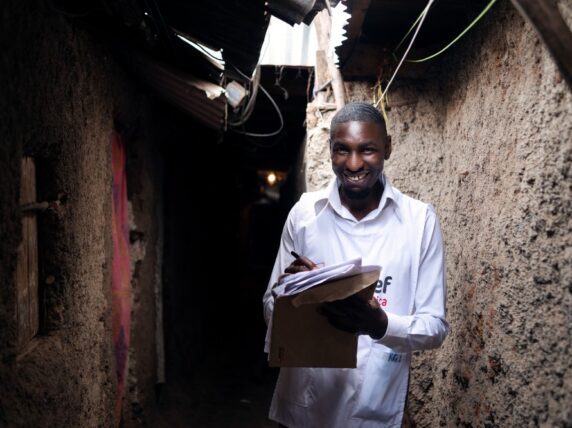

The persistence of colonial visual culture is especially glaring in international development. In charities and nonprofits, there’s a clear colonial hierarchy in the representation of beneficiaries and aid workers. Often, we are presented with an oversimplified and one sided portrayal of people in the global south, where the narrative is framed around unfortunate people in the need of ‘saving’. This perpetuates the Western stereotypical perception of developing countries and reinforces the ‘white saviour’ mind set.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsIt’s important to pause and take a look at the larger narrative these images are building, and re-imagine how we can, instead, shift towards empowering narratives. To achieve this, we must truly honour the people whose stories are being told, and refrain from approaching their stories through the gaze of an outsider, insensitive to their history, their living reality and experiences.

The altruistic acts of ‘White Saviours’ can be found throughout the development community in the west. Whether it’s Ed Sheeran and Stacey Dooley posing for ‘Comic Relief’ with some black children, or Bon Jovi’s Feed a Child campaign, the picture is consistent: a white celebrity, completely unaware of the history, context and nuanced realities of the people they are posing with, and some African kids cheering them on.

What’s common in all of these images, is a glaring absence of stories shared through the voices of the people being portrayed. These visuals do not portray how individuals are working to better their own situation. Instead they strip people of their agency and dignity, and show them as just waiting to be saved. Neither are they sensitive to nuances of local contexts. Such images only trigger feelings of pity, guilt and other-ness, disconnecting viewers from the people they set out to serve. They are not only unfair to the persons portrayed in the campaign, but also hinder long-term development.

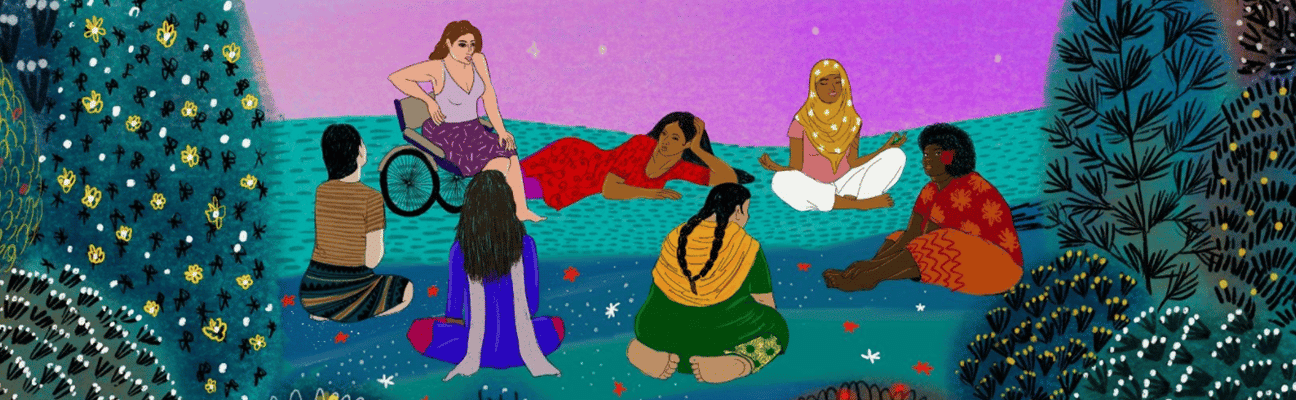

Every image feeds into a larger narrative. That’s why it’s important to ask: what is the larger narrative our images of choice are feeding into? Is the narrative further oppressing the oppressed? To shift these oppressing hierarchies, our images need to visualise justice, equality, radical love, collective power, support and community. Instead of depicting one community receiving resources from another, they need to represent indigenous knowledge and the exchange of resources. Our images need to talk about solidarity, not charity; power, not helplessness.

Visual communication checklist

To ensure responsible representation and avoid harmful stereotypes, here is a simple checklist for visual communication::

- Make sure you are not the hero of their story: An organisation can be an agent of change, enabling collaborative practices rather than perpetuating the hierarchy of ‘funder’ and ‘beneficiary.’ Doing so will ensure that people have the agency to engender change, inspire trust and drive decision making. After all, they know what’s best for their land, their people and their community.

- Engage local people in the decision-making process for the communication of your project: Recipients of aid are not passive people, they should have ownership and a voice in your project. Gain informed consent on how they would want to be portrayed and represented.

- Focus on solutions rather than the problem: This means not using pity inducing images of violence, poverty or hungry-disfigured bodies. Focus on what can be done to tackle the problems these people face.

- Focus on the power, capacity and skills of local people: Ask people what they bring to the table. Show local doctors, development workers, community organiser, nurses, farmers, crafts persons and teachers etc.

- Talk about an exchange of resources (rather than just giving): Ask yourself what you learned/gained from local people. This could be a new tool or skill, or different methods of managing, organising and leadership.

- Ensure diversity: Representation of a truly diverse group of people is crucial to ensure no community is invisibilized in the process. This includes representing indigenous people, as well as diverse identities, genders and people with disabilities.

- Be mindful of the different types of audience you have and the emotions you are triggering in them through your communication: Which emotion do you want to trigger? Is it empowering, constructive and hopeful?

- Use images that preserve the dignity of the people they portray: Do your images depict their story with dignity, sharing unique human experiences and feelings?

Many organisations are now talking about and educating people to this end. In 2012 SAIH Norway created a campaign called ‘Africa for Norway’, supported by the Norwegian Agency for Development Co-operation, where they simply turned the tables to drive the message home. The campaign video parodied beautifully how western charities often portray Africans in popular culture. Another great example would be “I must not make assumptions” by Live Below The Line, A charity based in Australia. And lastly, a special shoutout goes to one of my favourites, Barbie Saviour, an instagram account of a white barbie saving Africans.

In order to stop perpetuating white saviourism, we need to strategically shift the narrative towards love, hope, solidarity and connection. We need to re-imagine our choice of images to represent people in their power and the chain reaction of change that every individual is capable of bringing to the larger picture.