What Biden’s presidency means for international development

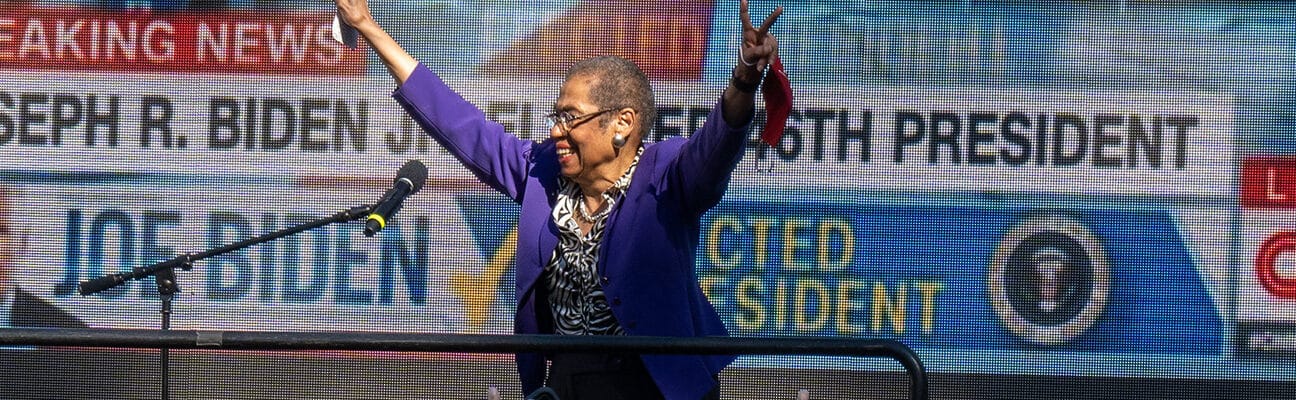

Joe Biden has been elected the 46th president of the United States, bringing to an end a tumultuous four years of Donald Trump’s presidency.

The last four years has seen the US adopt a more insular and abrupt foreign policy whilst international cooperation has taken a back seat to a perhaps overpromised, underdelivered, domestic agenda from Trump. America first, world second.

So what does a Biden presidency mean for international development, both in the UK and abroad.

Sexual and reproductive health and rights

In 2017, Trump reinstated and expanded the Mexico City Policy, more commonly known as the global gag rule, which prevents foreign organisations from receiving US federal funding if they provide abortion counselling, referrals, or abortion services, even in countries where it’s legal.

While there have been many iterations of this policy, enacted by previous Republican presidents, policy experts have said this one has been most restrictive, impacting over 1,300 global health projects. This has led to an increase in maternal deaths and has disproportionately affected harder to reach communities. Luckily the UK and other European countries stepped up to fill the void left by the Trump administration.

There is a sense now from the development community that they will find a natural ally under a Biden government, which is expected to reverse many of Trumps policies, including the global gag rule.

The climate crisis back on the US agenda?

Despite Trump’s repeated threats to cut “foreign aid”, Congress held him back. Elected officials understand the need for state funding for overseas aid, despite party loyalties. Climate on the other hand is, to quote our American friends, “an entirely different ball game”. The Republican Party has a chequered relationship with climate change. And while there have been some calls in recent time from sections of the Republican leadership for the US to do more on climate change, many activists have denounced this as nothing more than rhetoric.

In 2017, Trump announced that the US was withdrawing from the Paris Climate Accord – the global agreement to take immediate steps to tackle the climate crisis. And just days before the election, the US officially withdrew from the accord, making it the only country in the world to hold back from the global agreement.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsPresident-elect Biden has already committed to re-joining the Paris agreement, although he faces a considerable challenge if he wants to pass domestic legislation to fight the climate crisis. As of now, the Republicans control the Senate – one of two elected chambers of the US legislature. And while the Democrats control the House of Representatives, Biden needs cooperation from both houses if he is to pass any laws on climate action.

There is hope for the president-elect, albeit a slim one. As of now, the Republicans are in control of the Senate by two seats – a lead that could be lost when an election takes place in January for two seats in the State of Georgia. If the Democrats Senate is tied at 50 seats each, the vice-president, Kamala Harris, will get the deciding vote, which means that the Democrats will be in control of all three legislative powers – the House of Representatives, Congress, and the Presidency. This sort of control will allow Biden to follow through on his climate plan without much opposition at all.

Winning these seats will be a tough ask for the Democrats, however, with Republicans expected to win these seats back in January. It’s likely that Biden, a man that has built a reputation – and indeed a presidential campaign – on being able to bring people together, will have to try and work with a Republican-led Senate, unwilling to make any substantial moves on climate change.

Rebuilding the international system?

There’s much more to a Biden presidency than dismantling the policies bought in by Trump.

Back in March, the then-former vice president Biden wrote about the need for the US to “rebuild the international system” and restore peoples’ trust in free democracies.

Biden believes that restoring people’s belief in democracy at home strengthens democracies around the world. He plans to do this with education reform, restore voting rights for disenfranchised civilians, and reforming the justice system that leaves ethnic minorities at a disadvantage. He believes that from day one he will have the dual task of restoring people’s belief in the US democratic process whilst reinvigorating the international systems that champion open and free societies.

When I’m speaking to foreign leaders, I’m telling them: America is going to be back. We’re going to be back in the game.

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) November 10, 2020

Biden wants to “prove to the world that the United States is ready to lead again.” He has called for an end to the “forever wars” and states that under his leadership the US will end their support for Saudi-led war in Yemen – something that has failed to pass through congress under a Trump presidency.

Speaking to a conflict policy professional, the frustration of the last four years is apparent: “Their [the US] approach to international conflict has been confusing at times…Trump’s decision to rapidly draw down troops from Syria had an immediate and tangible impact on the lives of the people caught up in that conflict, yet he also chose to veto bipartisan legislation that would have ended US support for coalition forces in Yemen.”

Biden’s support for the end of conflict in Yemen can be a tricky one for the UK government to navigate. “This would be quite a shift in policy – one that would run counter to the recorded positions of government ministers to date,” a policy expert told us.

The effect of Covid 19 is apparent as the votes in the US are still being counted, a week after the in-person polls opened. But every media agency, including those loyal to the president and his agenda, have called it for Joe Biden. As the transition of power begins, we will keep an eye out for concrete policy positions that will define what type of presidency Biden wants. But in absence of concrete policy recommendations, one thing is apparent. Under his presidency, Joe Biden wants the US to be the leader of the “free world” once again – in his own words “back at the head of the table.”

Category

News & ViewsThemes

Politics