Commercial contracting: a lexicon

In cluster groups, donor meetings and Bond conferences, I hear the whispered small talk.

Whether it’s the challenge of NICRA not conforming to the ICR for a DFID AGA or a delayed PQQ because DFID are busy with the fallout from ASI, the sector thrives on acronyms and buzzwords.

Shortcomings

With many INGOs now undertaking commercial contracts a whole host of new terms and acronyms have emerged as common parlance in our sector. I already refer to the mechanism as CC whereby DFID often kicks off with a PIN followed hopefully by an EME or two. The PQQ of course has now become the SSQ – or just SQ if you are a really seasoned DFID supplier.

The ITT remains the main bid document, in which one really ought to mention VfM’s 5 E’s and throw in M&E for good measure. And surely there is always room for a little PbR?

I haven’t even got on to the elaborate acronyms the project title will be given, AL-SHABAAB being one of the more inventive ones I saw from a project officer in Somalia with too much time on his hands.

Lingo Bingo

The Americans are ahead of us in their understanding of the commercial contracting terminology, which is emerging as a result of how some INGOs are being treated in the consortia they form with the private sector primes, known in the US as Beltway Bandits. This interaction, while often positive with respect to the learning and delivery, is not always mutually beneficial.

Those familiar with the more evil end of the private sector spectrum, particularly on Framework Agreements, will have heard the term Bid Candy. This refers to organisations, usually INGOs or NGOs, included in the bid submission simply to make the consortium look good and win the tender. Some may have experienced the initial joy of winning, only to discover that INGOs are left out of the final project consortium or left with a considerably reduced scope of work or budget. One hopes that the new Standard Selection Questionnaire, with its requirement to break down the budget envelope between sub-contractors enables the commissioner to track this trend.

Speak and Spar

The key is of course negotiation and not relying on verbal agreements. INGOs are very comfortable with informal, participatory partnerships with fellow NGOs. Expectations and modus operandi are understood on both sides when it comes to grants. With commercial contracts, particularly private sector-led consortia, INGOs mustn’t make assumptions and rely too heavily on goodwill, especially where a partnership is untested. Negotiations do not need to be nasty, but they do need to be professional and as comprehensive as possible.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsPreparation is critical. Avoiding being treated as bid candy requires clear internal agreement on what a supplier wants. Don’t let a prime dismiss the need for a pre-teaming agreement or similar document. Know what you bring to the consortium and evaluate that internally in order to leverage what you want from the prime. This must be authorised from senior management and understood by those engaging in the negotiation. And prior to a partnership negotiation every INGO should know their red lines, beyond which you will politely walk away.

Finally, it is imperative to accept that sometimes it simply may not be worth investing in a particular tender. This doesn’t mean the community will not be served, merely that another supplier will assist them.

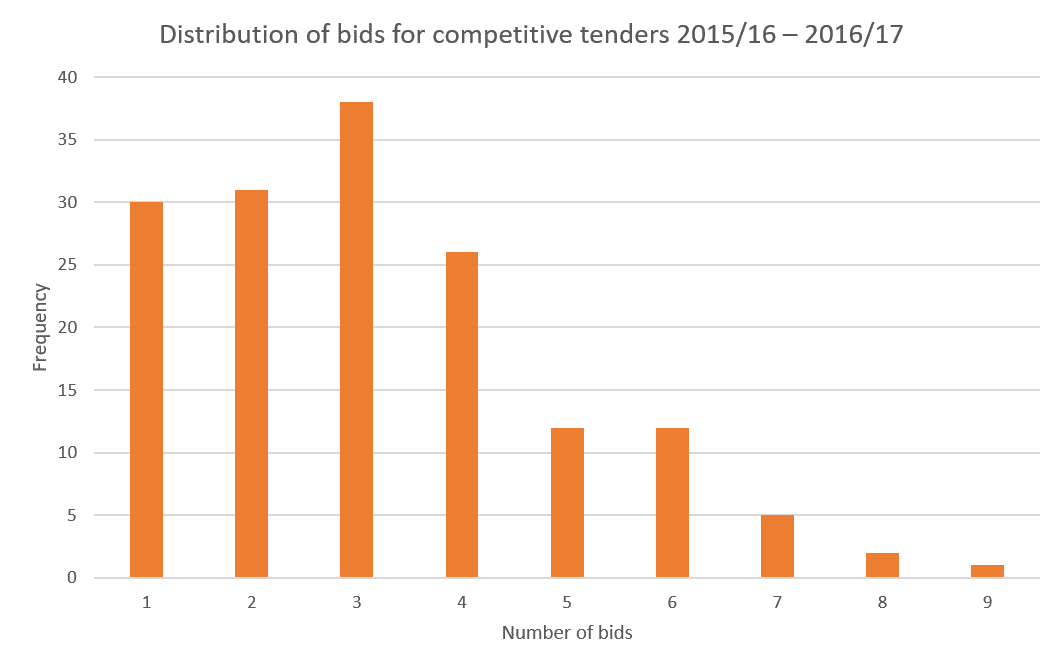

Earlier this year, the International Development Committee looked into DFID’s levels of competition for tenders published. The results were worrying, with 30 competitive tenders only receiving one bid application. No wonder then that DFID are keen to expand their supplier base.

However, I hope that this won’t lead to the introduction of another term from our American cousins – Column Fodder. This is where suppliers, whether INGOs or private sector primes, are encouraged by commissioners to bid simply to make up the number of bids submitted, no doubt to meet internal competition requirements with no intention to award the contract to them.

INGOs in particular need to be wary of bidding for commercial contracts as this is an expensive undertaking. Commercial contracts require additional time and staff, some different skills, an adjustment of processes and systems, greater investment in partnership building and a more critical review of agreements and contracts as well. And then there is risk – many INGOs haven’t even tracked the unrestricted funding going into cover unexpected costs on contracts. Column fodder isn’t for INGOs, it simply requires too high an investment.

Commercial contracting: a glossary

NICRA – Negotiated Indirect Cost Rate Agreement

ICR – Indirect Cost Rate

AGA – Accountable Grant Agreement

PQQ – Pre-Qualification Questionnaire

ASI – Adam Smith International

PIN – Prior Information Notice

EME – Early Market Engagement

SQQ – Standard Selection Questionnaire

SQ – Selection Questionnaire

ITT – Invitation to Tender

VFM – Value for Money

VFM’s 5 E’s – Economy, Efficiency, Effectiveness, Equity and Cost-Effectiveness

PbR – Payment by Results

Haniya will be delivering DFID commercial contracting essentials (21-22 September) and an advanced level training course on Winning and delivering DFID commercial contracts (25-26 September).

Haniya will also be discussing commercial contracting at Bond’s Funding for Development conference on 10 July. Get your ticket to hear about new trends in fundraising and network with institutional donors.

Category

News & Views