From rhetoric to action: urgent priorities for the new UK government on Official Development Assistance

The newly elected Labour government has come into power expressing a welcome promise “to rebuild Britain’s reputation on international development”.

The challenges the government faces in rebuilding its Official Development Assistance (ODA) programme – savaged by repeated cuts since 2019 – to support this promise are significant, especially as nearly a third of spending was diverted towards supporting refugees in the UK in 2023. Ensuring the UK can once again be seen as a reliable and ambitious development partner will require a clear plan to manage spending pressures and to properly resource the ODA budget.

Without these plans, more UK ODA cuts are likely, the UK will have little to offer at key global summits and in response to urgent humanitarian and development needs in 2024, and its manifesto promise will look like empty rhetoric.

It is important that the new government is clear-eyed about the challenges it faces in rebuilding the UK’s ODA ambitions and reputation. Since 2019, the UK’s ODA budget, and especially the programmes it funds overseas, have faced waves of savage cuts.

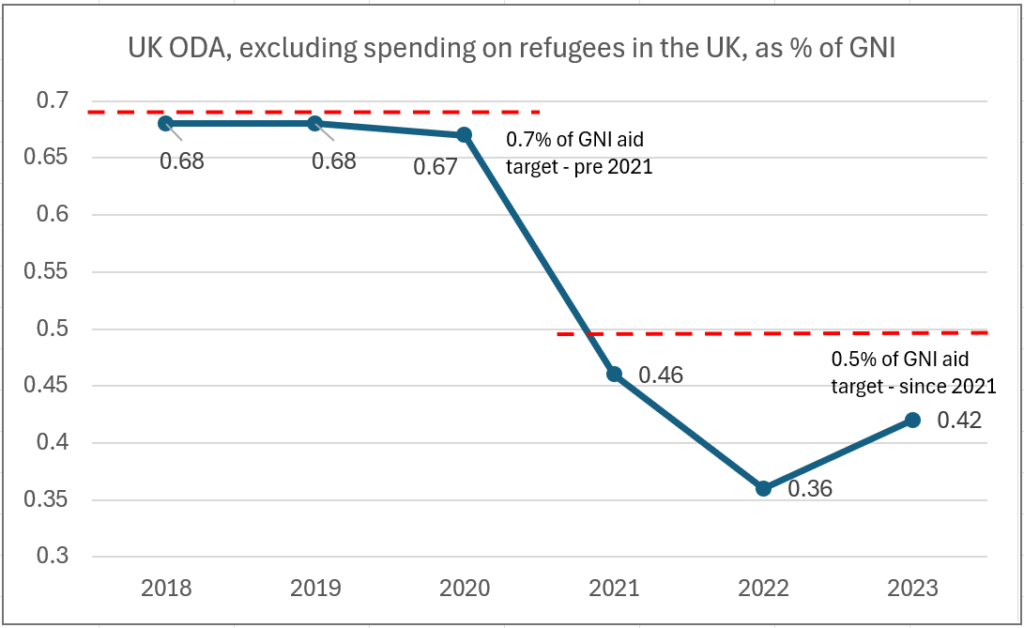

Overall levels of UK ODA were cut by £0.7 billion in 2020, due to COVID-19-related contractions in the UK economy, and another £3 billion in 2021, as the UK’s ODA budget was reduced from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income (GNI). In parallel, enormous cuts to ODA spending on ‘overseas’ programmes were made across this period as UK ODA allocated towards covering the costs of supporting refugees in the UK rose from £0.5 billion in 2019 to £3.7 billion in 2022.

Although total UK ODA was subsequently increased by almost £4 billion (to 0.58% of GNI) during 2021-23 – mostly due to additional resources allocated by HM Treasury to help manage these spending pressures – four-fifths of this uplift was swallowed up by the ballooning costs of supporting refugees in the UK (which reached £4.3 billion in 2023). As a result, total UK ODA excluding spend on refugees in the UK was £3.6 billion (or 25%) below 2019 levels, and just 0.42% of GNI in 2023 (compared to 0.68% in 2019).

The results of these ODA cuts and reallocations have been devastating and have literally turned the clock back more than a decade on support provided by the UK to low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

UK ODA for the poorest and most vulnerable countries has been hit particularly hard, with UK bilateral ODA focussed on the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) more than halving during 2019-22. UK ODA has also been savaged in many sectors critical to poverty reduction and leaving no one behind, including bilateral spending on education (cuts of 58% since 2016, at lowest level since 2009), health (cuts of 39% since 2020, at lowest level since 2011), water & sanitation (cuts of 78% since 2018, at lowest level since 2009) and humanitarian support (cuts of 42% since 2019, at lowest level since 2014).

The new UK government therefore faces the challenge of urgently reversing these trends in UK ODA, so that it can scale up its response to global needs and rebuild its global reputation on international development. Doing so will also allow it to make new financial commitments to key global process in 2024, including the UN Summit for the Future (September), the climate COP (November) and the replenishment of World Bank-IDA (to conclude in December).

Reversing these trends will also allow the UK to scale up responses to major humanitarian emergencies in contexts such as Gaza, Sudan, Ukraine and Yemen, where needs are growing and the UK’s response has been severely damaged by ODA cuts, including a further reduction of 20% in total bilateral humanitarian support in 2023.

However, a key challenge is that ODA spending on refugees in the UK is expected to remain high in 2024, given that the arrival of asylum seekers on small boats across the English Channel has been increasing in recent months. The continuation of recent policies to inflate levels of reported ODA spending on refugees in the UK, recently criticised by the OECD-DAC and the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI), will make this issue even more challenging.

It is therefore vital that in the early weeks and months of its administration the next government takes the following steps:

- Allocate the funding required to ensure that UK ODA budget is at least maintained at current levels – 0.58% of GNI – in 2024, to avoid ODA cuts, support the UK to make new commitments at key global summits, respond to humanitarian crises and help with the challenge of returning to 0.7% in the coming years

- Review and reduce the categories and volumes of spend on refugees in the UK reported as ODA in order to reduce its demands on the UK ODA programme and meet the OECD-DAC’s requirements to ensure this ODA spending is reported in a ‘conservative’ manner. The required support to vulnerable refugees should increasingly be provided by departments other than FCDO.

- Increase the proportion of UK ODA focussed on LDCs and other low-income countries, so that this spending can have the maximum impact on supporting those who need it most.

- Urgently scale-up UK ODA on humanitarian support, to at a minimum meet the outgoing government’s commitments to spend £1 billion in this sector in 2024, so that the UK can respond to urgent needs in contexts such as Gaza, Sudan, Ukraine and Yemen, and to a range of other neglected crises

- Refocus UK ODA on basic services – including health, education, social protection, nutrition and water and sanitation, so that this spending can better support people living in poverty and facing marginalisation

Without rapid action to take these steps, the new UK government’s ambition of rebuilding its global reputation and partnerships with low- and middle-income countries will quickly be exposed as rhetoric not backed up by action.

Category

News & ViewsThemes

UK aid