Can the public really be taken on a “journey” to engage with global poverty?

How do the public become engaged with global poverty?

Campaigning, fundraising and communications strategies are often built around the assumption of an “engagement journey”, whereby the public move from no engagement to marginal actions, like reading or listening to news about global poverty, to more meaningful forms of engagement, like signing a petition, attending a protest or donating money to anti-poverty organisations.

But new research from the Development Engagement Lab suggests that the public don’t move in a straight line from low to more meaningful engagement. Driven by a number of factors, people jump around the various engagement categories, and often tend to “stick” in certain categories more than others, where they might be harder to shift.

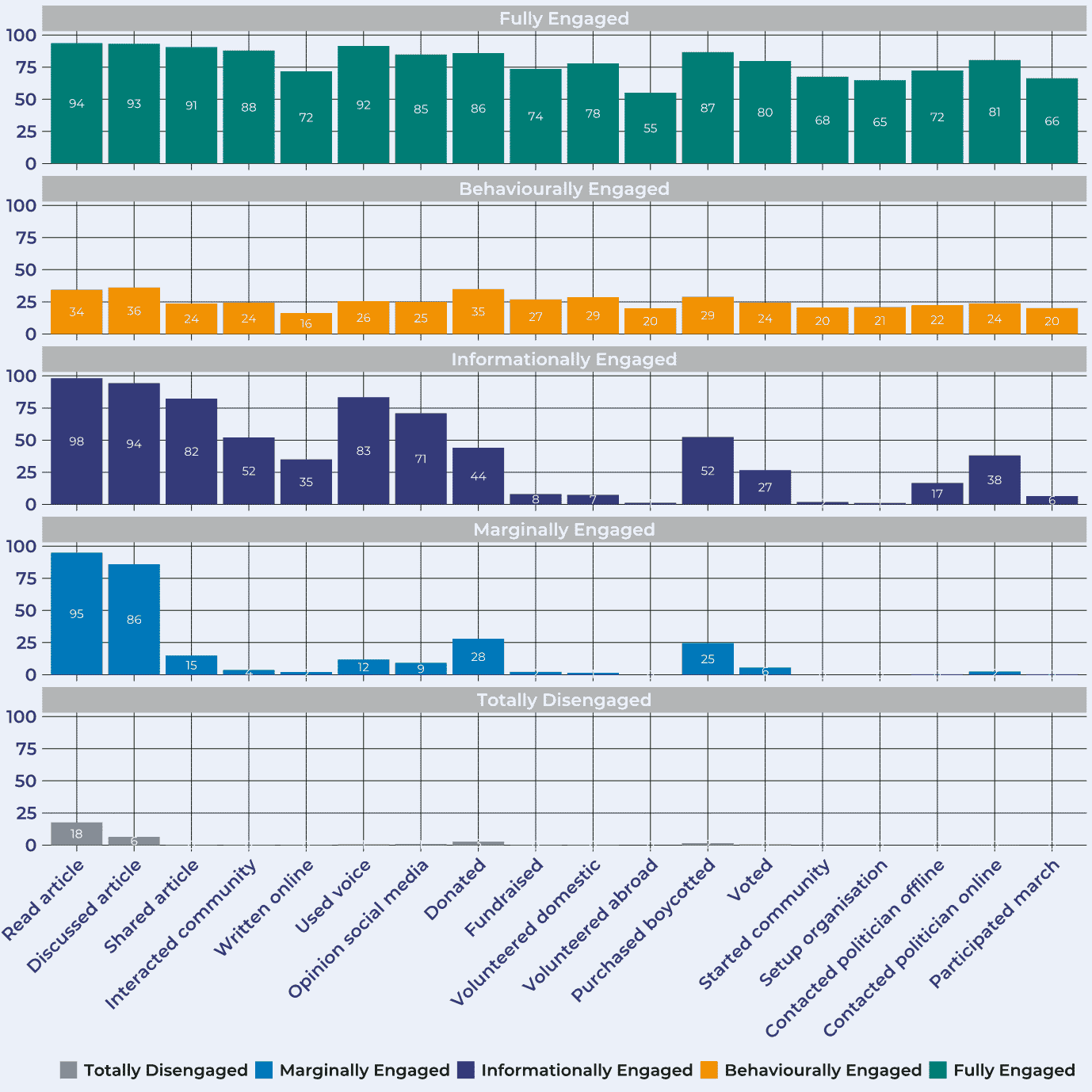

Using panel data from Germany, France, the United Kingdom and the United States, we divided respondents into the Development Engagement Lab’s five engagement groups based on their behaviours: Totally Disengaged (46% of respondents), Marginally Engaged (33%), Informationally Engaged (13%), Behaviourally Engaged (6%) and Fully Engaged (2%). Examining the groups in this way revealed two unusual patterns, both of which challenge the way we think about engaging the public.

Segment “stickiness”

So, are the public ‘fixed’ in their engagement? Do they become more or less engaged? While we do see evidence of change over time, it tends to be slow.

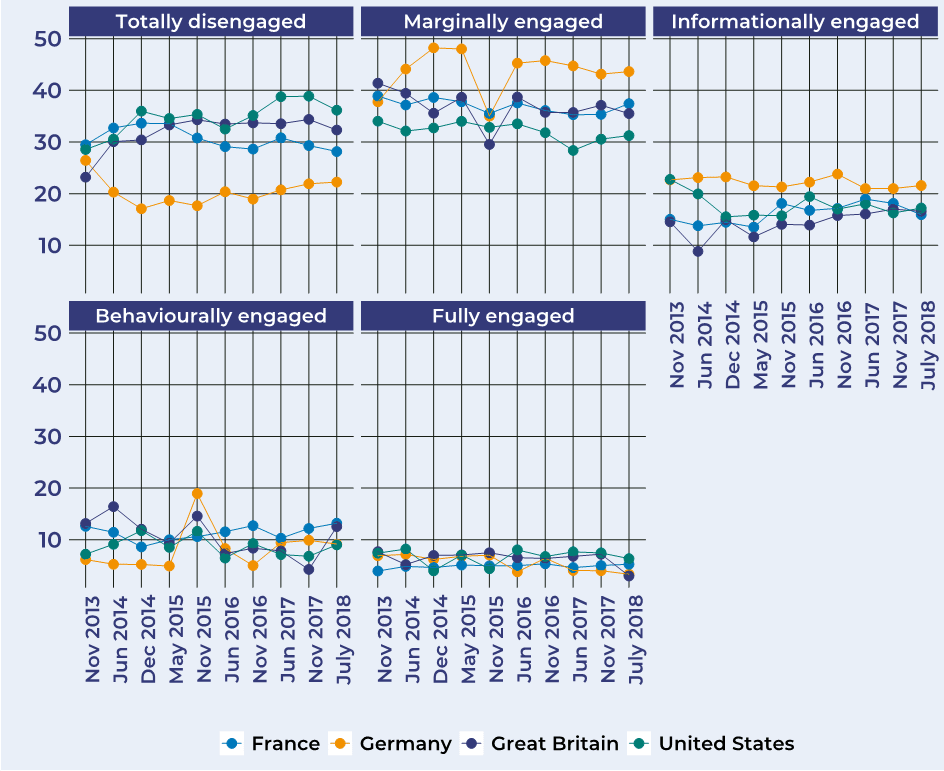

Figure 2 shows small movement within engagement groups. While the overall percentage of the Marginally Engaged group remains constant, it’s important to note that there may be regular entry and exit from other engagement groups.

Looking more closely at this individual-level movement, we see that the majority of respondents fall into the Totally Disengaged and Marginally Engaged segments. It’s also clear that these two groups are extremely stable or “sticky”; respondents “stay in their lane” over time. When they do move, respondents move both up and down the engagement ladder. This means that even highly engaged people can slide back down again. An organisation’s most engaged followers, sponsors or donors can be lost.

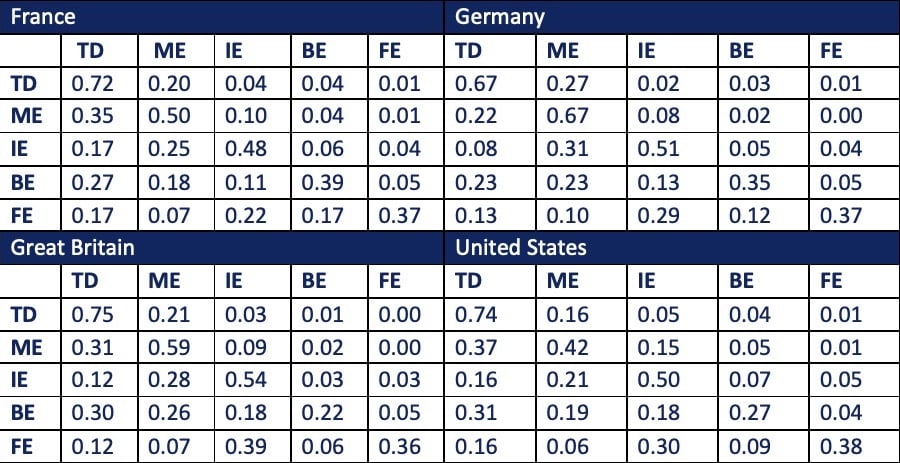

In the table above, we look at how likely respondents in each segment are to move. The closer the number is to 1, the greater the probability a respondent will remain in the same segment.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsWhat is also striking is that the more engaged segments are less stable, meaning respondents are more likely to move in and out of them. In other words, it’s harder to keep people Behaviourally and Fully Engaged.

What Drives Engagement?

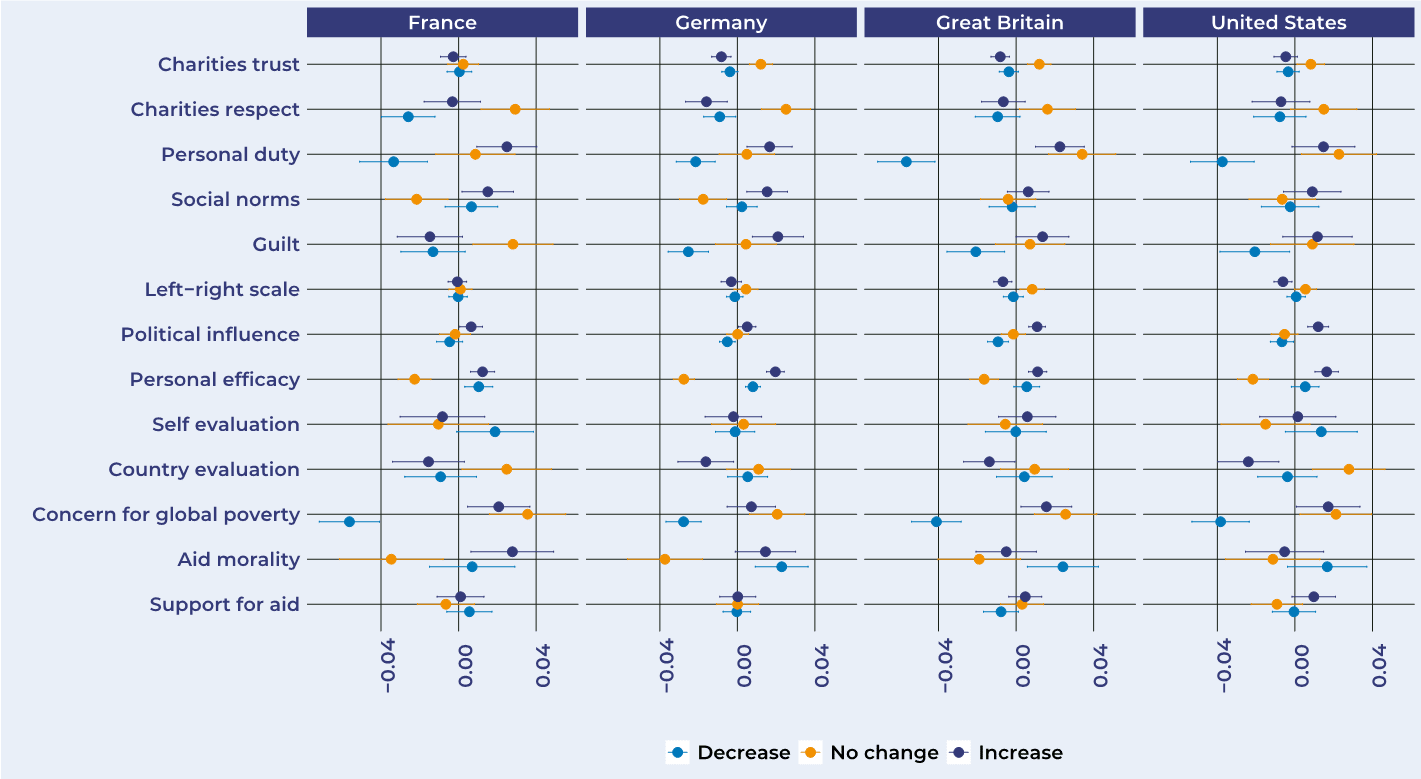

Just as there is no single direction in the engagement journey, there are different reasons driving engagement down or up. Our research shows that what drives people down does not necessarily drive people up.

For example, concern for global poverty keeps people from moving down from Marginally Engaged to Totally Disengaged, but does not move them up from Marginally Engaged to Informationally Engaged, Behaviourally Engaged or Fully Engaged. Being concerned about poverty is not enough to increase engagement: it actually keeps people Marginally Engaged.

Guilt yields similar results: people who feel guilty are less likely to become Totally Disengaged, but the effect of guilt on becoming more engaged is inconsistent. The most consistent driver is personal duty: respondents with a sense of personal duty are less likely to disengage, and have a higher chance of becoming Informationally, Behaviourally or Fully Engaged.

We draw two conclusions. First, the average engagement journey is from Totally Disengaged to Marginally Engaged, who then tend to stay that way. Second, the Marginally Engaged are an important audience for development NGOs, not least in terms of their relative size. They are an “eligible” audience to deepen engagement.

However, donor publics don’t behave in the same way as supporters. Communications and engagement opportunities may work well for supporters, but they may not work for a varied and diverse public. This may require investing in a more versatile (e.g. creative venues and touchpoints supported by new technology), broader (e.g. moving beyond extreme poverty to align with climate, global health and related issues) and bespoke sets of activities that fit a diverse public.

Join us on 9 December for Where do the public stand on aid and global poverty in the midst of Covid-19?, a free webinar where you’ll get the latest insights on British audience engagement in the current crisis from the Development Engagement Lab’s latest research.

This blog is based on data originally published in Development in Practice, in a paper titled, ‘Not one, but many publics’: Public engagement with global development in France, Germany, Great Britain and the United States,’ authored by Jennifer Hudson, David Hudson, Paolo Morini, Harold Clarke and Marianne C. Stewart.

Category

News & ViewsThemes

Public Support