5 existential funding challenges for large INGOs

It would be foolish to forecast the impacts of the Covid-19 crisis on northern INGOs with certitude. The ability to achieve the collective mission(s) of INGOs will change for sure – in both positive and negative ways.

On the positive side, the pandemic has once again highlighted our global interdependencies. So we might see a shift in normative thinking by citizens, politicians and investment funds on the need to address climate change, inequality and other global issues. On the other hand, we could be entering an even more isolationist, nativist way of thinking that exacerbates, rather than addresses, our global challenges.

As Oxfam International’s former director of strategy, I’ve seen that northern INGOs’ sustainability has been a problem for some years, in terms of their relevance and finances. The current crisis merely accelerates this challenge.

Having recently studied the long-term income trends of seven of the larger INGO families, I’ve observed five main challenges to INGOs’ sustainability.

Challenge 1: growth and decline in income (pre-Covid-19)

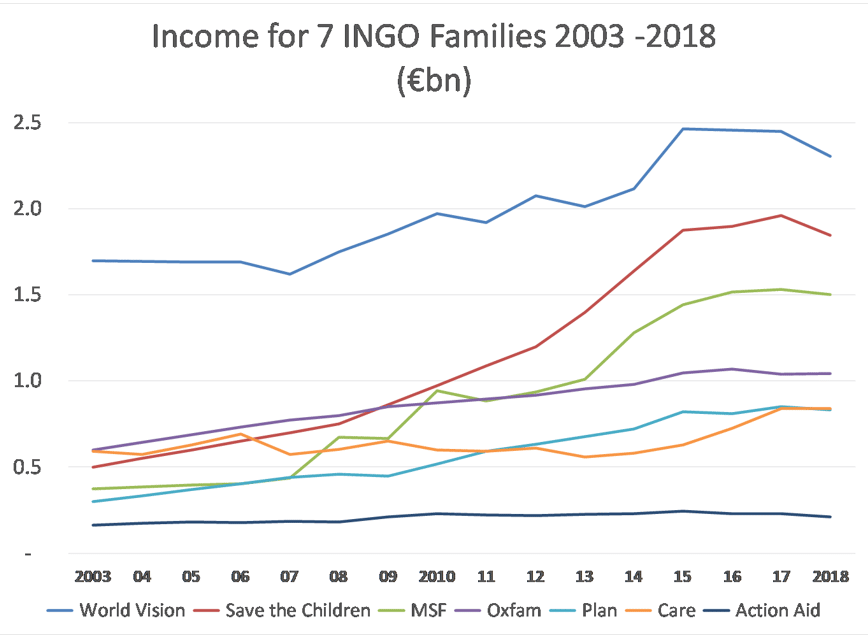

INGO income grew at a steady rate between 2003-2009, followed by a more rapid growth until 2015/16, followed by a plateauing and then a decline.

Challenge 2: income growth increased dependency on institutional funding

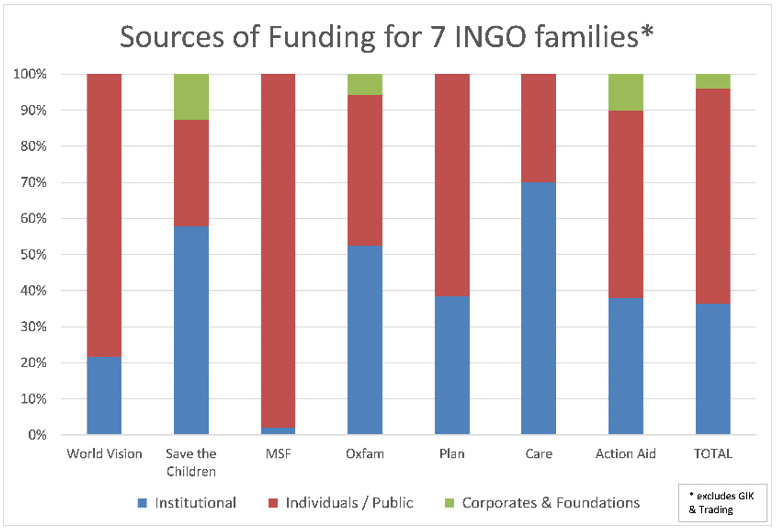

The growth has come primarily from significant increases in institutional donor or bilateral development co-operation contracts. Institutional funding is now more than half of many large INGOs’ income. This has created growth, but reduced strategic flexibility.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsIt has also necessitated the use of unrestricted or light restricted public-fundraised income to cover the extra costs of superstructures. In some cases, dependency on a few core institutional donors has meant that the destiny and continued existence of the INGO, or individual members, is inextricably linked to political decisions outside their control.

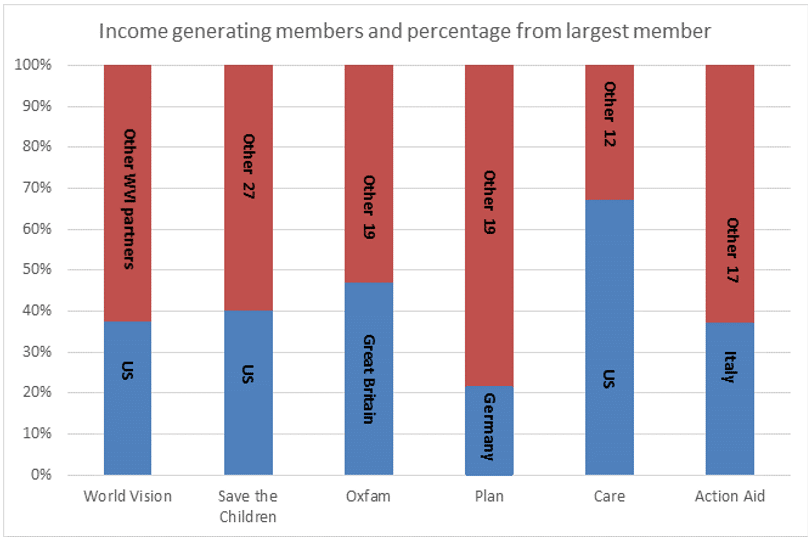

Challenge 3: the “big one” member provides most of the income in NGO families

Almost all the NGO “families” of (con)federated NGOs are dependent for a significant amount of their income (as much as two thirds in some) on the largest member of their federation/confederation. A decline in that “big one” member’s income disproportionately affects the whole family – mainly because the “big one” funds such a large share of the secretariat or global co-ordination body, country offices, innovation, research, etc. Thus a sudden decline in their income causes more problems than a sudden decline in, say, the ten smallest members.

Challenge 4: competing markets for funding

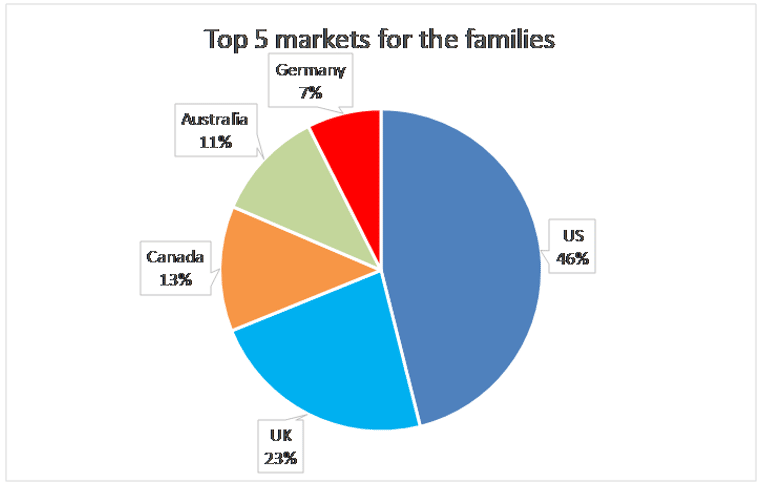

These INGO families are mostly dependent on five markets for public and institutional funding: the US, UK, Canada, Germany and Australia. They are also competing in the same second tier markets (in terms of volume of income): Scandinavia, Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy.

Northern INGOs were already facing pre-existing headwinds: political and public attention for international development has declined. The rise of nativism in the political environment means that ruling political parties have less of a mandate or are not as interested in the issues. Only five OECD DAC donors now give 0.7% of GNI or more for development co-operation and humanitarian issues.

The public fundraising markets have also been saturated in these countries and the “cost of acquisition” of new individual donors has ground down returns on fundraising investment. Humanitarian crises have increased, but are frequently slow onset, protracted and seen as political issues, making it hard to get media attention and public awareness.

The economic crisis caused by Covid-19, and the need to service hugely expanded government debt will put further pressure on development co-operation budgets – in the near and medium term. The endowment funds of the major foundations have also taken a hit. Recruiting new individual givers at a faster rate than existing ones are “lapsing” will get harder. Nationalism and hostile media are also driving trust in INGOs down.

Challenge 5: what is INGOs’ relevance?

Leaders of member organisations in INGO federations have been wrestling with the “relevance” challenge for some years. Where do INGOs fit in a world where most countries are (or were about to become) middle-income countries? Where southern civil society is (rightfully) claiming its space from northern INGOs? And where the ability to get big advocacy-led impact is dependent on local rootedness for legitimacy and accountability?

Primarily humanitarian and faith-based NGOs seem to be coping with this challenge better than their peers.

Consequently, northern-founded NGOs may be able to weather the immediate storm – but the underlying fundamentals, which were a challenge for their financial sustainability before the Covid-19 crisis, have intensified.

Now is the time for boards and executive leadership teams to make the tough decisions that have been looming for the last five years (or more). In my next blog for Bond, I’ll explore critical questions for INGOs to ask themselves and possible ways forward.

Sign up the Bond newsletter for more insights and opinions on international development.

You can also read Barney’s full report on the existential funding challenge for northern INGOs.

Category

News & ViewsThemes

Funding